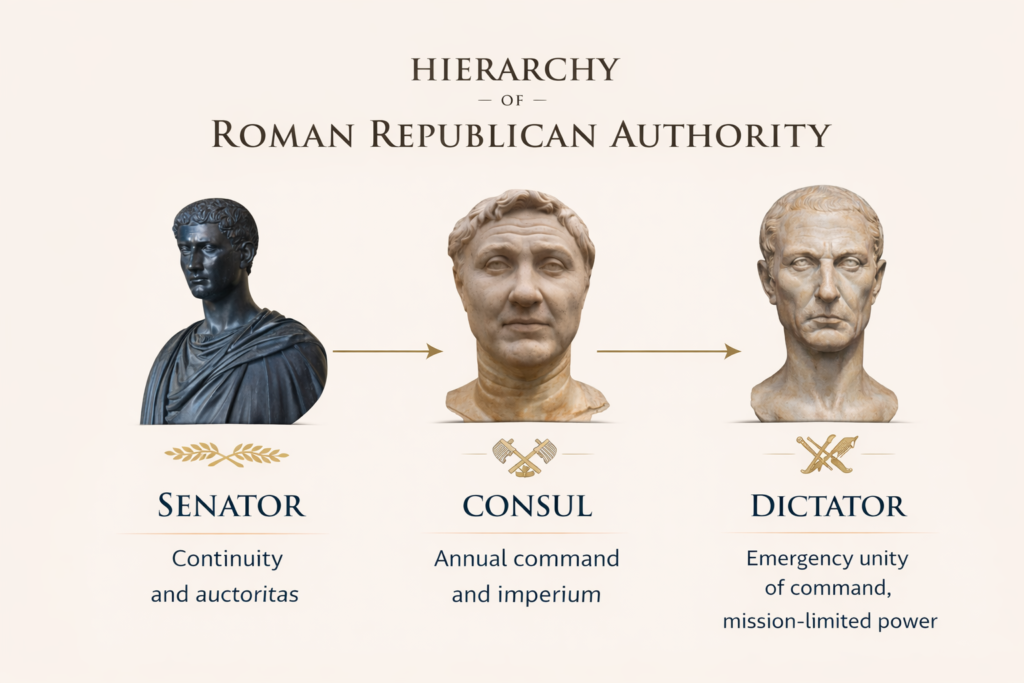

Senator, Consul, Dictator : Roles and powers in the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic did not concentrate authority in a single permanent ruler. It distributed power across offices designed to move at different speeds: consuls supplied executive force and immediate command, senators supplied continuity and collective judgment, and the dictator supplied extraordinary unity of command in moments of acute danger. The system’s stability rested on a Roman distinction that shaped political life for centuries: imperium (the legal power to command) and auctoritas (the prestige that makes counsel carry weight).

The Senator

The Republic’s standing council and long memory

A senator was a member of the Roman Senate, the central deliberative body of the ruling elite. A senator was not a “minister” with a fixed portfolio; he was part of a corporate institution whose strength lay in seniority, experience, family standing, and the shared discipline of precedent.

Core functions

- Deliberation and direction: Senators debated public business and issued formal opinions and resolutions. These were often framed as “advice,” yet they could guide policy with immense practical force because they expressed the Republic’s collective elite judgment.

- Continuity: Magistracies were annual and quickly replaced; the Senate endured, preserving policy memory across decades—treaties, rivalries, fiscal habits, and the reputations of commanders.

- Statecraft behind the scenes: In practice, senatorial influence was strongest where continuity mattered most—diplomacy, finance, provincial oversight, military logistics, and the broad framing of Rome’s priorities.

How one became a senator

Membership evolved over time, but senatorial status was closely tied to public service and elite recognition. The censors—guardians of civic rank—played a decisive role by revising the senatorial roll, enrolling men deemed worthy and removing those judged unfit. The result was a council that functioned not merely as a meeting, but as a curated political order.

The Consul

The Republic’s annual executive and commander

The consuls were the Republic’s highest regular magistrates. Crucially, Rome elected two each year, and their term was one year. This was not administrative convenience; it was constitutional philosophy. Power should be strong enough to act, but too brief and too shared to harden into kingship.

Core powers

- Imperium: Consuls held the Republic’s highest ordinary command authority, especially in war—raising forces, leading campaigns, and enforcing discipline.

- Civic leadership: They presided over major political procedures, convened assemblies, and often set the tempo of public business.

- Agenda-setting: They could summon the Senate and bring matters forward for debate, translating military and political realities into decisions that required senatorial backing.

Why two consuls mattered

Collegiality was a built-in restraint. Each consul was a counterweight to the other; rivalry could be disruptive, but it also prevented the office from becoming a single, unchecked command. A successful consul therefore needed more than boldness. He needed legitimacy, resources, and political cover—often secured through cooperation with the Senate.

The Dictator

Extraordinary authority for extraordinary moments

In the early and middle Republic, a dictator was an emergency magistrate appointed for a specific crisis or task: a catastrophic military threat, internal disorder, or an urgent public necessity requiring unified command. The dictatorship was meant to be exceptional, temporary, and purpose-bound—a tool to save the Republic, not replace it.

Defining features

- Concentrated imperium: The dictator’s authority eclipsed ordinary magistrates for the duration of the mandate, allowing decisive action without the delays of divided command.

- A defined mission: The office was typically tied to a clear objective—defeat an enemy, stabilize a crisis, conduct an essential act of state.

- Short duration: Tradition sets a limit of six months, though dictators often resigned earlier once the purpose was fulfilled.

- Deputy command: The dictator appointed a subordinate, the master of the horse (magister equitum), to assist with operations, especially military ones.

A later transformation

The dictatorship’s original logic belonged to a Republic that still believed exceptional power could be safely contained by custom and resignation. In the final century of the Republic, Rome’s political storms altered the meaning of the office. What had been a temporary remedy could be stretched into a weapon of domination—an evolution that reveals not only ambition, but institutional strain under imperial-scale pressures.

In one sentence each

- Senator: A guardian of continuity whose collective authority shaped policy through precedent, deliberation, and control of the Republic’s long-term direction.

- Consul: The annual executive commander who acted with imperium but relied on senatorial backing to make command sustainable.

- Dictator: An extraordinary magistrate granted concentrated imperium for a defined emergency, meant to resign when the crisis ended.

Roman Republic Authority Registry

Senator, Consul, Dictator

Office • Scope • Limits • Insignia • Historical Note

Senator

Office

Member of the Senate (Senatus), the Republic’s standing council of senior public men.

Scope

Custodian of continuity. Deliberates on state business. Frames policy through collective judgment. Sustains the Republic’s long horizon—war finance, diplomacy, provincial oversight, and institutional precedent.

Powers in practice

- Converts experience into direction.

- Shapes what is politically feasible by granting or withholding collective support.

- Establishes the Republic’s governing “memory” through debate and settled custom.

Limits

No single senator commands by office merely by sitting in the chamber. Authority depends on reputation, alliances, and the Senate’s corporate standing.

Insignia

Not defined by a unique executive emblem. Status is expressed socially and politically—rank, dignity, precedence, and the right to speak within the Curia.

Historical note

Senatorial authority is best understood as auctoritas: a weight that makes “advice” operate like practical direction, especially when magistrates require resources, legitimacy, and continuity.

Consul

Office

The Republic’s highest regular magistrate. Two are elected each year. Term: one year.

Scope

Executive command in war and governance in peace. Presides over major political business. Convenes the Senate and drives the public agenda.

Powers

- Holds imperium (command authority).

- Leads armies and conducts major operations.

- Presides, initiates, and executes state action.

Limits

- Collegial restraint: one consul checks the other.

- Temporal restraint: the year closes quickly.

- Political restraint: sustained action usually requires senatorial support, especially for funding, logistics, and long-term strategy.

Insignia

Curule dignity; lictors; fasces—symbols that make command visible and public.

Historical note

The consul embodies the Republic’s “present tense”: swift action, immediate decisions, and public responsibility—powerful, but deliberately short-lived.

Dictator

Office

Extraordinary magistrate appointed for a defined crisis or essential task. Not a normal annual office.

Scope

Unified command when the Republic requires speed and coherence beyond ordinary checks.

Powers

- Concentrated imperium for the mandate’s duration.

- Subordinates ordinary magistracies for the specific mission.

- Appoints a deputy: the magister equitum (master of the horse).

Limits

- Purpose-bound: appointed for a clearly defined necessity.

- Time-bound by tradition: commonly limited to a short term, and expected to resign once the task is completed.

- Dependent on legitimacy: the office is meant to protect the Republic, not replace it.

Insignia

Heightened symbols of command; elevated precedence in the civic order; the visible language of emergency authority.

Historical note

In early Republican logic, the dictatorship is a constitutional instrument of rescue—exceptional power with an exit clause. In the late Republic, that logic is strained, and the office becomes a sign of deeper political breakdown.

Registry Summary

Senator — continuity and auctoritas

Consul — annual command and imperium

Dictator — emergency unity of command, mission-limited power