The January 11 1944 Independence Manifesto: A Moroccan act of state, written before the world was ready to hear it

On 11 January 1944, Morocco did not merely protest. It formulated. It did not simply grieve. It argued. The text known as the Independence Manifesto was composed with a rare discipline: the discipline of a state speaking in the idiom of states. It addressed authority without servility, history without nostalgia, and the international order without naïveté. In a few pages, it transformed a national aspiration into a diplomatic proposition.

What endures is not only what the Manifesto demanded, but how it demanded it. Its architecture is deliberate: a preamble that establishes legitimacy, determinations that translate legitimacy into program, and signatures that convert program into responsibility. The document does not seek pity; it seeks recognition.

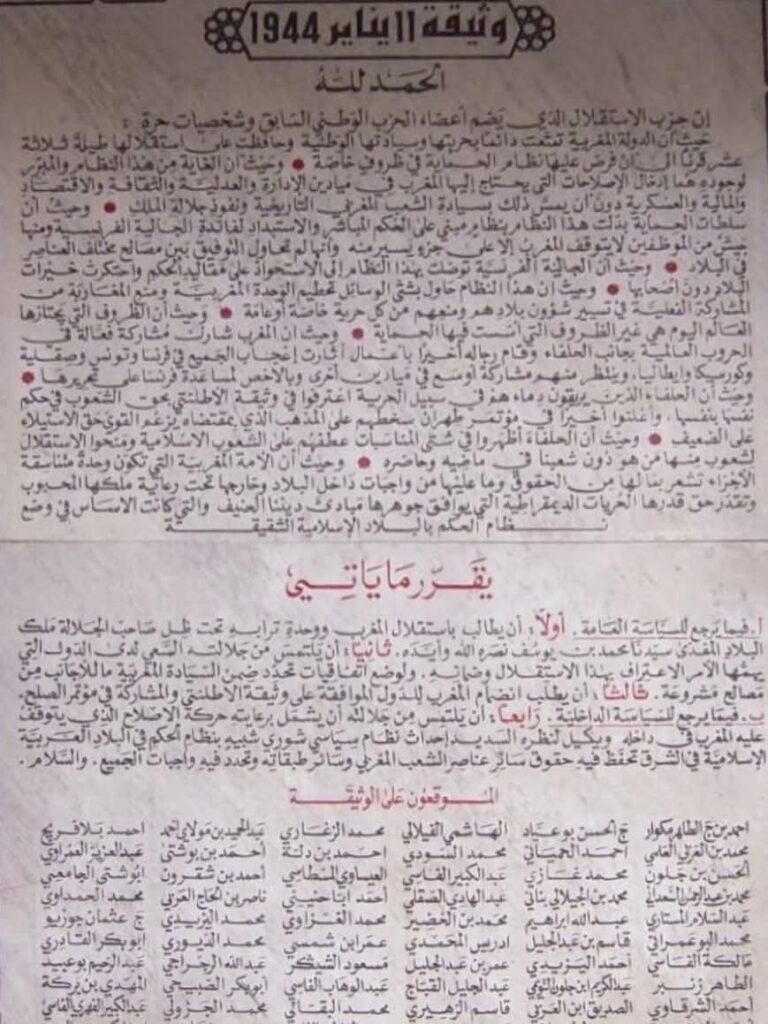

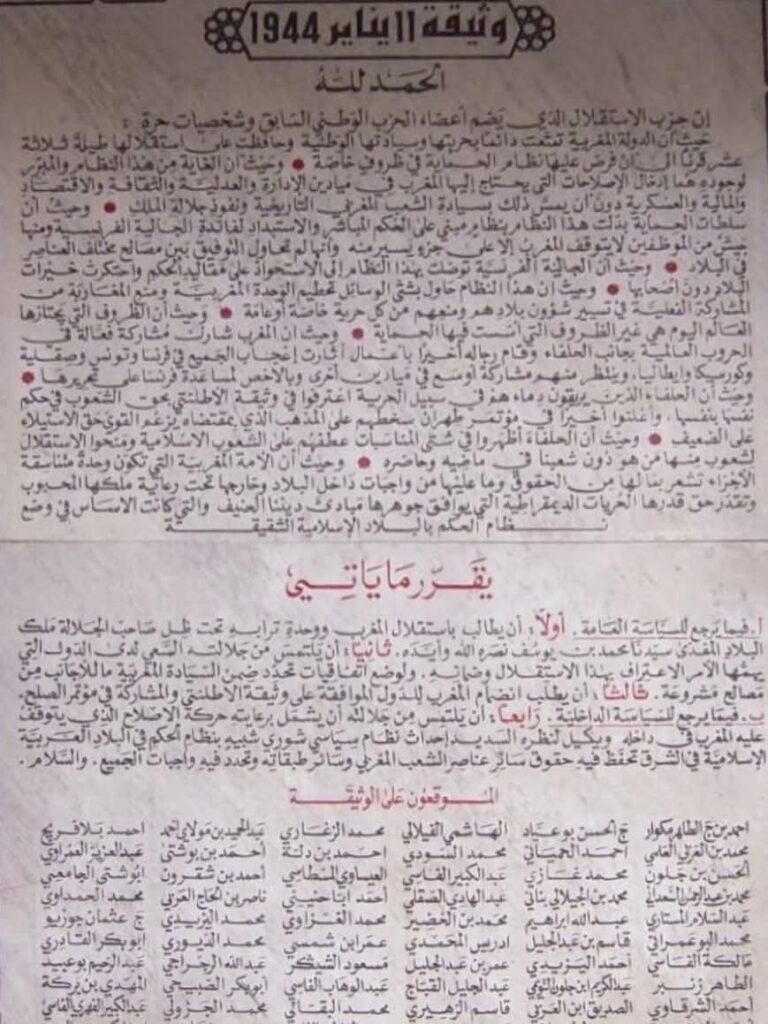

A preamble built like a case file

The Manifesto begins where sovereign arguments begin: with continuity.

Morocco is presented as a polity whose identity predates the protectorate and therefore cannot be reduced to an administrative arrangement. The protectorate, initially associated with promises of reform and protection, is described as having drifted into a system that constrained Moroccan agency and redirected the country’s political, economic, and cultural life away from national control.

This is not rhetorical excess. It is a juridical posture. The text is structured as a demonstration: an original premise, a breach of that premise, a series of consequences, and the necessity of remedy. Even when indignation surfaces, it is contained within a logic that resembles a memorandum more than a pamphlet. That restraint is itself a political act.

The diplomatic instinct

Addressing the postwar world before it arrives

The Manifesto’s most modern instinct lies in its timing. Drafted while the Second World War was still raging, it reads the future with acute attention: it anticipates an international order in which legitimacy would increasingly be measured by principles rather than by possession.

It draws upon the language of self-determination and the moral grammar that the Allied cause had placed into circulation. It evokes the idea that participation in the collective struggle against tyranny cannot be reconciled, indefinitely, with the indefinite maintenance of tutelage. In doing so, it does not merely appeal to conscience; it appeals to coherence.

This is diplomacy in its mature sense: the art of forcing power to recognize the meaning of its own declared values.

Throne and nation

Sovereignty as continuity, not improvisation

A decisive element of the Manifesto is the way it anchors the demand for independence to the Moroccan monarchy. Independence is not imagined as an abstract rupture, nor as a vacuum in which institutions must be invented from scratch. It is framed as the restoration of full sovereignty under the legitimate sovereign, Sidi Mohammed ben Youssef, later King Mohammed V.

This is more than a gesture of loyalty. It is constitutional reasoning. The text implicitly declares that the Moroccan state did not disappear under the protectorate; it was constrained. The monarchy is presented as the axis of unity, continuity, and international personality. In that framing, the nation is not rebelling against the state; it is summoning the state back to its full stature.

There is, here, a careful political elegance: to demand independence while preserving the symbols that make independence intelligible.

The determinations

A program of sovereignty, not a slogan

When the Manifesto turns from argument to decision, it does so with economy. It does not multiply demands; it clarifies essentials.

It calls, in substance, for an independent Morocco whose unity is respected, whose sovereignty is recognized, and whose political life is reorganized on consultative foundations. The requested independence is not portrayed as isolation, but as entry into the family of nations on terms consistent with modern statehood: responsibility, participation, and institutional renewal.

What is striking is the balance. The text is at once national and international, traditional and reformist, principled and practical. It offers a future that is neither a return to an idealized past nor a surrender to imported models. It proposes a Moroccan modernity expressed in Moroccan terms.

The signatures

A ledger of courage and accountability

At the bottom of the document lies its most human component: names.

The Manifesto is widely remembered as having been signed by sixty-six figures of the national movement. A signature on such a text is not an ornament; it is a risk assumed in public. It transforms an idea into a commitment that can be answered by interrogation, imprisonment, or exile. The list of signatories is therefore not a formality. It is a civic ledger.

One name, in particular, carries a lasting resonance: Malika al-Fassi, often cited as the only woman among the signatories. In a political culture frequently narrated through male leadership, her presence inscribes a quieter truth: national history is also written by those whom institutions too often render invisible.

Delivery as political theatre

Why presentation mattered as much as content

The Manifesto was not written to remain in Moroccan hands alone. It was presented to the colonial authorities and brought to the attention of foreign representations. That choice is essential to its meaning.

It turned a domestic claim into an international question. It placed Morocco’s demand inside the arena where recognition is negotiated: not only on streets and in prisons, but also in chancelleries, reports, and diplomatic memory. The authors understood that sovereignty is not merely seized; it is also narrated, defended, and made legible to the world.

In this sense, the Manifesto was an act of protocol as much as politics: a controlled presentation of legitimacy.

The afterlife of a state paper

When a text becomes ceremony

With time, the Independence Manifesto became more than a document. It became a national rite, a recurring moment in which Morocco remembers itself as a community of continuity and will.

Such documents endure because they do two things at once. They answer the immediate crisis of their moment, and they offer future generations a language with which to interpret that crisis. The January 11 text does precisely that. It is a bridge between eras: between protectorate and sovereignty, between national movement and state restoration, between a contested present and an intended future.

Closing reflection for The Kingdom of Decrees

The January 11 1944 Manifesto deserves to be read as a formal instrument of legitimacy. It does not simply denounce; it establishes. It does not only request; it declares. It stands at the intersection of three disciplines that define statecraft at its most serious: the memory of sovereignty, the craft of international argument, and the architecture of institutional renewal.

In the gallery of texts through which nations reclaim their voice, this Manifesto holds a distinctive place. It is not a decree issued from power. It is a decree-like claim addressed to power, composed with the dignity of a people who had already decided what they were, and who were prepared to teach the world how to name them.

Reading the Manifesto as protocol, strategy, and national choreography

If the Manifesto is a text, it is also a method. It teaches, implicitly, how a nation can transform a historical grievance into a claim that institutions can carry, diplomats can repeat, and future generations can inherit without distortion.

The document as a lesson in protocol

Protocol is often reduced to ceremony, flags, seating, precedence. The Manifesto reminds us that protocol is also the grammar of legitimacy. By choosing a formal structure—preamble, determinations, signatures—the authors adopted the codes through which states recognize one another. They did not speak as a crowd; they spoke as a polity. This was a strategic refinement: it made the demand harder to dismiss as agitation, and easier to register as a question of status.

In this sense, the Manifesto is a precedent in the strict meaning of the word: it sets a pattern for later acts of national assertion—measured tone, clear hierarchy of principles, and an insistence on continuity rather than improvisation.

The signature list as political geometry

The list of signatories is frequently read as a roster. It is more accurately read as architecture. It distributes the burden of the statement across a collective, transforming individual conviction into a public front. The number itself matters less than the intent: to show that the claim is not the passion of one voice, but the converging will of multiple reputations, cities, professions, and circles of influence.

That is why the presence of a woman among the signatories, often cited with Malika al-Fassi, carries such weight: it punctures the convenience of a single narrative and enlarges the civic portrait of the movement. It also signals that a national cause, to be durable, cannot remain socially narrow.

A quiet brilliance: sovereignty framed as restoration

Many independence texts describe a birth. The Moroccan Manifesto describes a return. This is not a semantic luxury; it is a political advantage. A “return” implies rightful title, continuity of institutions, and an illegitimacy in the interruption itself. It gives the claim a calm confidence: the authors do not ask to be invented; they ask to be restored to themselves.

That framing also protects the state from the dangers of sudden rupture. It invites reform, but within a continuity that preserves unity—the most fragile asset in any transition.

The monarch as axis of state intelligibility

The Manifesto’s insistence on the sovereign is sometimes misunderstood as mere symbolism. In the language of international relations, it is intelligibility. A state that can point to continuity of authority, to a recognized apex, and to a unifying institution is a state that other states can recognize without fearing fragmentation.

The text therefore binds national will to an institutional anchor, making independence not a leap into uncertainty but a reconfiguration of authority into its proper, autonomous form.

The hidden audience of the text

Not only the colonizer—also the future arbiters of recognition

The Manifesto speaks to more than the immediate power on the ground. It speaks to the global witnesses who would later read, classify, and remember Morocco’s status. It is drafted as though it anticipates dossiers, cables, memoranda, postwar conferences, and the slow machinery through which legitimacy becomes accepted fact.

This is why its tone matters. It avoids excess. It avoids theatrical insult. It constructs a record. It behaves as if it expects to be quoted. And a document that expects to be quoted is already practicing diplomacy.

What the Manifesto implies about statecraft

Three principles that outlive the moment

1. Political claims must be legible in international language.

Even when the cause is moral, recognition is procedural. The Manifesto adopts procedural dignity: it makes the demand readable by outsiders who do not share the intimate pain of the protectorate but understand the rules of status.

2. National unity is not a sentiment; it is a design choice.

By binding throne and nation, by emphasizing unity, the text treats cohesion as an active construction. It refuses the temptation of internal rivalries because it understands that divided legitimacy invites indefinite tutelage.

3. Reform is not postponed—it is incorporated.

The text does not separate independence and governance as two unrelated chapters. It implies that sovereignty must be accompanied by institutional renewal, otherwise sovereignty becomes a flag without capacity.

A protocol lens for The Kingdom of Decrees

How to present this document as a “registry entry”

If you are curating state papers, precedence, and the formal vocabulary of authority, the Manifesto can be featured not simply as “a historic demand,” but as an instrument of legitimacy with identifiable protocol attributes:

- Document type: National manifesto framed as act of state

- Structure: Preamble → determinations → signatures

- Legitimacy anchors: historic sovereignty, unity of territory, monarchic continuity

- Diplomatic posture: appeal to principles of the emerging world order; demand for recognition

- Civic function: a public ledger of accountability through signatories

- Afterlife: annual commemoration; foundational narrative of throne–people union

In that framing, the Manifesto becomes part of a larger series: the texts through which nations declare themselves, not by shouting, but by writing in a form the world cannot pretend not to understand.

Final cadence for this continuation

The January 11 1944 Manifesto is often summarized as a demand for independence. That summary is true, but insufficient. The document is also a demonstration of political maturity: it proves that Morocco did not only desire sovereignty—it knew how to speak it. It understood that statehood is an art of form as much as an assertion of right: a disciplined voice, a coherent program, and a public assumption of responsibility.

A nation becomes impossible to ignore when it masters the language by which the world keeps its records. Morocco mastered that language on paper—before it could fully master it on territory.